Posters and placards

Good posters exist… only in the domain of trifles, of industry, or of revolution.

Maurice Talmeyr, La Cité du Sang, 1901

These revolutionary placards… form an immense and unique composition, one without precedent, we believe, in the history of books. They are a collective work. The author is Monsieur Everyone…

Alfred Delvau, Les Murailles Revolutionnaires de 1848, 1852

Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project

The banner, the placard, the sticker, the flyer, the poster and the mural are intrinsic to political discourse, a discourse which intensifies in the campaign and specifically in the demonstration. The traditional trades union banner, often intricately woven, is a symbolic materialisation of a movement and a struggle, and has something of the status of a religious icon or battalion flag.

Whether carried in cloth or card or paper, just as on a wall, each artefact is a form of simple messaging, a few words cast as a claim, a comment, a curse, a question. Messages use rhyme and wit, often coupled with an image, perhaps a cartoon, a logo or a photograph, in reaching for effect. The poster or placard is a visual as well as verbal form: the sign is there to be seen, in order that the statement it makes might carry more widely, to more people than a single voice could.

Its combination of word and image, designed to assert and persuade, mean that in form and function the poster has much in common with advertising. Yet the demonstrator’s placard is often no more than a square of cardboard and a stick. It may be idiosyncratic, if not unique, or may be one of thousands cheaply printed and duplicated. The memorable or witty phrase is designed to be remembered and repeated, and may be photographed and replicated in different media, in newsprint, on tv or by phone.

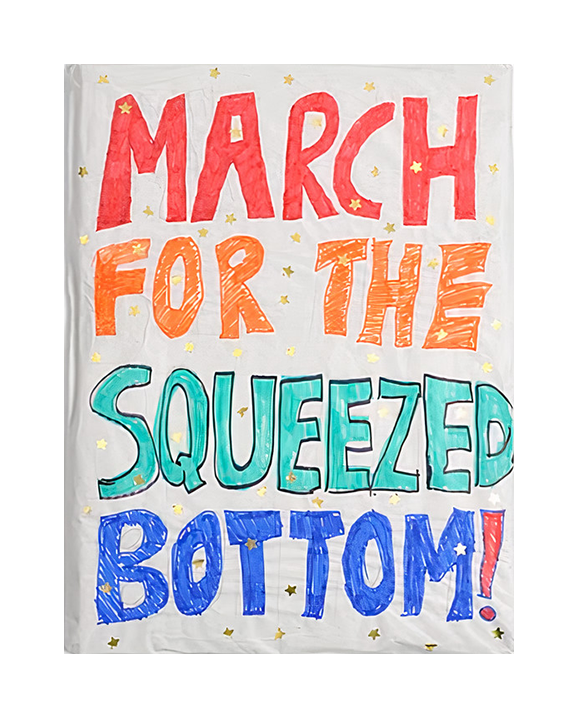

‘We didn’t buy anything special, but improvised using a piece of cardboard from an old box, which we covered in flipchart paper and attached to a broom handle… Everyone helped to make the placard…

Susie came up with the slogan – inspired by the idea that the poor would be the ones who would lose out most by the cuts. There’s been a lot of talk about the ‘squeezed middle’ but we were concerned about the impact of what was happening in areas such as Tower Hamlets where Susie works with community groups.

Katherine drew the lettering on the placard. Then Susie and Misty coloured in the letters and helped to decorate it with sticky dots and stars. Making the placard was quick and fun – very much a team effort. Done on the spur of the moment.

We wanted to celebrate the fun that can be had through demonstrating, as well as to reflect the British sense of humour, to create something memorable and appealing, and to make people smile.’

Save Our Placards, 2011

Historically what’s interesting about signs is that they were about the mass demonstration, the collective, and so you would see the same union poster held by everyone. Now it seems to be much more about the individual, so you’ve got people writing personal messages.

Simon Roberts, interview, in Diane Smyth, ‘Signs of the times’, 2012

Photographs

Those who don’t have a poster or placard at a demonstration have a camera. The demonstration is staged with documents, and is documented in turn even as it takes place. Others carry photographs, and will be photographed in turn carrying them.

About one in four demonstrators in Paris… had their smartphones up, recording as they marched, chanted or struggled through a haze of tear gas. Demonstrations are produced and curated as they unfold, becoming a series of ‘scenes from a demonstration’, with hundreds of director/participants live-streaming or waiting to upload content from their phones at the end of the day.

Jeremy Harding, ‘Among the Gilets Jaunes’, 2019

I think of the people I spoke to, and of one man in particular. He will not remember that I spoke to him. (He must have spoken to so many). He will not remember telling me how his brother died. (He must have told the story so many times). He will not know that because we spoke I remembered his brother’s name. He will not know that because of the banner he carried I one day recognized his brother’s face in the newspaper. He will not know that because I read about his brother in the newspaper I revisited my photographs, looked up the histories behind the banners. What is it like to be told your bother has died in custody? He will not know (I would like him to know) that because we spoke I followed a trail of names captured in unprinted negatives or discarded photographs and read what I could about those I can never meet: Joy Gardner, Kingsley Burrell, Ricky Bishop, Sean Rigg, Seni Lewis, Sheku Bayoh, Thomas Orchard, and Jimmy Mubenga.

John Comino-James, Shout It Loud, Shout It Clear, 2017

Photographs show people being so irrefutably there and at a specific age in their lives… Photographs state the innocence, the vulnerability of lives heading towards their own destruction, and this link between photography and death haunts all photographs of people… Photographs turn the past into an object of tender regard.

Susan Sontag, On Photography, 1977

In the aftermath of the attacks on the Twin Towers in September 2001, photographs of those lost were pinned to fences, walls and shopfronts around Ground Zero. They were appeals for information which became a form of documentary evidence, and then ‘an enduring protest, a collective scream’.

They were necessarily photos of time both past and lost, of weddings, barbecues and other family occasions, and at the same time negative images of a future they would never have, which would never exist. In this they have something in common with the photos carried by the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo in Buenos Aires, Argentina: pictures of the disappeared, images of past lives deployed in the present in the hope of future restitution, reparation and reconciliation.

The media reporting of representative democracy puts many different images of politicians into circulation everyday. Most are devised and taken by news photographers and television camera operators, and selected by newspaper and programme editors.

The significance of Instagram is precisely that it allows for the production and posting of images by or on behalf of political actors themselves. It’s a staging of self, its purpose to make a figure – a person signified by an image – appear before an audience and, often with a caption or some words of commentary, to set it into a specific cognitive frame such that it will be interpreted in a particular way. It also serves as demonstration of a certain form of tech-based social and communicative competence, of a politician’s facility with the contemporary.

Karin Liebhart and Petra Bernhardt’s study of Alexander Van der Bellen’s Presidential election campaign in Austria in 2016 showed how he used Instagram variously as a visual diary, allowing supporters to follow his campaign, and to engage in it in different ways; as a way of making direct contact with voters, including the inevitable selfies; in order to publish background stories of his personal, extra-political activity, at sports events, for example, or with his family; as a way of taking and clarifying a position on different issues; to report the talks and meetings in which he was involved with other politicians, as well as to report and disseminate his other media work.

Photography and electoral appeal

What is transmitted through the photograph of the candidate are not his plans, but his deep motives, all his family, mental, even erotic circumstances, all this style of life of which he is at once the product, the example and the bait. It is obvious that what most of our candidates offer us through their likeness is a type of social setting, the spectacular comfort of family, legal and religious norms, the suggestion of innately owning such items of bourgeois property as Sunday Mass, xenophobia, steak and chips, cuckold jokes, in short, what we call an ideology.

A full-face photograph underlines the realistic outlook of the candidate… Everything there expresses penetration, gravity, frankness: the future deputy is looking squarely at the enemy, the obstacle, the ‘problem.’ A three-quarter face photograph, which is more common, suggests the tyranny of an ideal: the gaze is lost nobly in the future, it does not confront, it soars, and fertilizes some other domain, which is chastely left undefined. Almost all three-quarter face photos are ascensional, the face is lifted towards a supernatural light which draws it up and elevates it to the realm of higher humanity; the candidate reaches the Olympus of elevated feelings, where all political contradictions are solved.

Roland Barthes, Mythologies, 1957